The first notice of my land came in 1835, when surveyors passed along the North line of my South forty, which is a section line. They noted good timber on the ridges and actually saw some small fields along Meadow Creek near it’s mouth at the Middle Fork of the Little Red River, just a couple miles SW of here.

This particular parcel was homesteaded by Earnest Bilke in 1916. He cleared a field and built a house on this land. Several years later he traded land (a common thing in those days) with a man called Daddy Richardson. Mr. Richardson built a new house and farmed this place for a number of years, clearing about five acres on the ridge (where my pine woods is today), growing cotton, corn, and sorghum. When I bought this place there was still a rock foundation and chimney where the cooking pan for molasses had been set up. Richardson farmed until 1936, then left for California without even trying to sell it. It went back to the state for taxes. In 1963 it was purchased for said taxes, $30.00, by a land company made up of two local ranchers and two Mountain View businessmen.

In the Spring of 1973 I borrowed a horse from a friend and rode across a one-hundred acre piece of land that was for sale for $100 per acre. It had been logged recently and looked very dry, but I kept riding down an old unused logging road until the timber got better and I came upon a pine grove, which I knew was evidence of an old field. I figured that if there had been a field, then someone must have lived here, and if someone had lived here then there must be water. I rode the horse down past where the pond now stands, and found evidence of a year-round spring. I then rode over the ridge to where it drops off into Bear Pen Hollow. Since the leaves were on the trees and the whole place was like a jungle, I had to shinny up a tree to see the great view to the West. Then and there I decided that this was the land for me. I rode back to the owner of the 100 acre parcel and found out that the place with the spring on it belonged to Robert Linville. He and his land partners had recently sold some land to some hippies, and they had a feeling that land was about to start selling. After some haggling they agreed to sell me this 40 for $145.00 per acre, which was on the high side for unimproved land at that time.

A name seemed to be in order for this place, so I chose Bear Pen Farm, since about 15 acres of my land lay on the side of this steep and rugged holler.

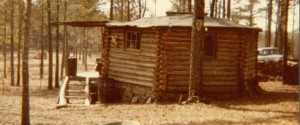

That Fall I started to build a six-sided log “Hogan”, twenty feet in diameter, as a temporary structure until I could build a bigger house. This would prove to be such a comfortable home that it would be seventeen years before the bigger house would be finished.

Author Archives: smith

The Hogan

Today, January 9th, 2012, we tore down and burned our old cabin, the six-sided log “Hogan” that I built when I first bought my land back in 1973.

I moved onto this land in October of ’73, after a summer of driving 18-wheelers to make my first land payment. My friend Tom Wilson loaned me a 12-foot tipi to live in while I was building a log cabin. The idea for the six-sided design came from a place called the Indian Health Camp at nearby Oxley, Arkansas. There they had built a number of very small (12-ft) hogans for guests to stay in. I was fascinated by the pattern of poles in the roof and the roundness, as opposed to squareness of it, and decided to build a bigger version, 20 ft in diameter and tall enough to walk through the door upright.

As soon as I got my tipi up I started cutting and peeling logs for my cabin. Luckily my cabin site was in the middle of a three-acre pine grove, since most of the ten-foot logs had to be carried by hand to the work site. Since most of the logs were from six to eight inches in diameter I figured 12 for each wall—that’s about 100 logs, which all had to be cut, carried to the work site, peeled with a drawknife and stacked in a rack for drying. I also peeled the tops of the trees I cut, down to about three inches in diameter, so I would have poles for the roof.

I left my poles and logs on the drying rack through the next summer, which I also spent driving big rigs. When I came off the road in October, I was ready to start building

.

I had already built the stone foundation pillars, so the walls went up pretty quickly. My only power tool was a heavy old Homelite ZIP chain saw, so the notching was pretty rough and funky. By Spring I was ready to start on the roof. Hogans have a unique roof structure. You lay a pole from the middle of one wall to the middle of the next wall, then fill in behind it with shorter and shorter poles until you get the the corner. Then when that group of six poles are in place, you repeat the process. When I got close to the middle, I

skipped every other log and wound up with a five-foot equilateral triangle-shaped hole. In a traditional Hogan this would be the smoke hole for the central fire. I got a sheet of ¼” plexiglass and made a skylight. Since I had no electric power at all in those days this skylight kept my little cabin from being dark and gloomy. The room was always filled with a glorious light from above, especially at night with the moonlight shining in.

In the spring of 1975 I was able to move in. Things were pretty basic in those days—a kerosene lamp for light, a battery-powered radio for entertainment, an old Servel gas refrigerator, a wood stove for heat. Sometimes I would go for three or four days without seeing another person. In November of 1977 Maria moved in with me, and began to apply a lady’s touch to the place. She cleaned up all the empty oil cans and trash in the yard, made curtains for the cabinets, and really turned the place into a comfortable and unique home. Before long we got a small 12-volt television that we hooked up to our truck to power it, then some solar panels and a house battery.

This little cabin that I built as a temporary shelter wound up being home for fifteen years. After we finished our new log home the Hogan became my leather shop. In 2007 hurricane Ike passed through here as a tropical storm and blew a big ash tree over on the cabin, severely damaging the roof. I had a sawmill on the farm at that time, and I sawed the lumber that I would need to replace the whole roof, planning on doing it in February, when we usually have a spell of dry weather. But then in January 2008 we were hit by a devastating ice storm (see related story) that kept me busy for over a year with cleanup. By this

time the leaking roof had caused the floor to rot, so we made the difficult decision to tear the old Hogan down. Since Jed and Austin were both home to help, we got a good fire going on the brush pile and with much trepidation I drove the forks of the tractor through the wall of our former home. The comfy home that took a year to build was gone by sunset.

PIGS

I guess we started raising pigs about thirty years ago. I figured I could raise two pigs, sell one to pay for the cost of pigs and feed, and butcher the other one.

At first I started doing it the same way I had always seen it done. I fenced in a pretty good size hog lot out of woven wire and built a wooden pig house so they could get out of the weather. We would feed the pigs wheat bran, corn chops, garden and table scraps and lots of skim milk from our cow. When the pigs reached around 250 lbs I would sell one and get set up for butchering. I used the same method that has been done in the Ozarks for years. I learned it from watching my neighbor, Lonnie Lee butcher his hogs. We built a fire under a 55-gallon barrel full of water, and set up a pulley and rope system to raise the hog and lower it into the water. When the water was almost to a boil, I would shoot the hog between the eyes with a .22 rifle and quickly put a chain loop around it’s leg, pull it off the ground with my truck and sever the aorta with a butcher knife to get a good bleed. Then we would dip the whole hog into the barrel to cause the hair to slip, lay the hog on a home-made table, and scrape all the hair off with knives. When the hair was off, I would hang it, remove the viscera and internal organs, saw the carcass in half from tail to shoulders, and leave it hanging overnight to chill. I always try to butcher on a night when it will freeze. Not only is it important to cool the meat quickly, it is much easier to cut up meat when it is partially frozen.

For several years we tried the traditional method of preserving most of our meat through salting and smoking. This involves injecting the meat with brine, smothering the meat with salt, then after a time, smoking the heck out of it. You wind up with hams and shoulders that will keep without being frozen, but meat that is impossible to eat without soaking in water to remove some of the salt. It didn’t take too many years of this to figure out that a freezer would be a good thing. We bought a used freezer and paid a neighbor to keep it at her house (she had electricity). We continued to scald and scrape our hogs for a few more years until I figured out that the only reason to keep the skin on the hog was as a way of preserving the meat. Then we started skinning rather than scraping. No more smoky fires and dangerous scalding water. With a sharp skinning knife two of us can snatch the hide off a hog in about half an hour.

It only took a few years, though, to see that keeping hogs in a pen is an environmental disaster. I could see that they were wearing a hole in the ground from their constant rooting and wallowing. Not only that, but it was very expensive to buy feed, which of course they needed every day. That is when I discovered a new method of raising hogs. Now when we buy a little feeder pig we put it in a temporary pen in the same pasture with whatever

calves I have on hand at the time. The calves are usually fascinated by the pig and spend a lot of time communing with it through the fence. It only takes a few days for the animals to bond—then I can release the pig and it spends the rest of it’s happy life roaming the farm with it’s bovine pals, grazing on grass and finding acorns and all sorts of goodies in the woods. Even though it can fit under the barbed-wire fence that is the boundary of our farm, the pig will NEVER get out of sight of the calves, so there is no danger of it finding it’s way to our nearest neighbor, a half-mile away.

Since I have been teaching guitar and fiddle at the local school one day a week, I haven’t had to buy ANY feed. One day’s lunch tray scrapings from 130 students is enough to feed a pasture-raised pig for a week! Now when I see the crater down in the woods that marks the spot where the hog pen used to be I just shake my head. We live and learn…………….

The Great Ice Storm

The Great Ice Storm

I never really saw an ice storm until I moved to Arkansas in 1972. Growing up in Northern Illinois I saw plenty of snow every winter, but seldom did it rain while the temperature was at or below freezing. But the Ozark Mountains are situated in an interesting place, weather-wise. Here we are apt to get huge amounts of moisture blowing up from the Gulf of Mexico, only to crash into frigid Canadian Northers sweeping down out of the Great Plains. When the dense cold air forces it’s way under the warm moist air, and rain occurs, we can get truly spectacular, and sometimes devastating ice storms.

Just such an event occurred in the first week of January, 2009. It started to rain on Tuesday, a fairly steady rain with the temperature at about 26 degrees. Soon every twig and branch had a coating of ice, and it continued to build up through the day and all that night. By Wednesday morning we knew we were in trouble. Several trees had uprooted and fallen on our fences, branches were coming down everywhere, and still the rain fell and the temp remained the same. Wednesday night it sounded like a war zone outside. Tops of  pine trees would load up with ice until the tree would either uproot or the trunk would snap 15 or 20 feet off the ground. Every few seconds we would hear a terrific POP followed by the smashing sound of tons of ice crashing to the ground. Oak, ash, pine and even hickory trees lost branches and tops until hardly a single

pine trees would load up with ice until the tree would either uproot or the trunk would snap 15 or 20 feet off the ground. Every few seconds we would hear a terrific POP followed by the smashing sound of tons of ice crashing to the ground. Oak, ash, pine and even hickory trees lost branches and tops until hardly a single  tree on our farm was undamaged. By Friday most of the ice had melted away, and our farm looked like a tornado had hit it.

tree on our farm was undamaged. By Friday most of the ice had melted away, and our farm looked like a tornado had hit it.

The ice storm covered a huge area. Parts of Eastern Oklahoma, Northern Arkansas, Southern Missouri and even Western Tennessee and Kentucky were affected. In our county alone over 1000 power poles snapped under the weight of the ice. Some people were without power for as much as three weeks. As a volunteer firefighter I spent a lot of time out in our community helping to clear the roads of all the fallen trees and branches. It was eerie driving through Fox after dark with all the houses dark, just maybe a glimmer of a candle here and there through a window.

the weight of the ice. Some people were without power for as much as three weeks. As a volunteer firefighter I spent a lot of time out in our community helping to clear the roads of all the fallen trees and branches. It was eerie driving through Fox after dark with all the houses dark, just maybe a glimmer of a candle here and there through a window.

One of my jobs as a firefighter was daily service of the generator that provides power for the police and fire department radio repeater, located at the AETN tower about three miles from my house. When I got there on

Thursday afternoon, after the sun had come out and things had begun to thaw, there were 100 lb chunks of ice falling off the 1000 ft tower. I had to dash from my truck into the relative safety of the generator shed, service the engine, then run back to the truck as bombs of ice fell all around me. It was terrifying!

The way that our community pulled together was heartwarming. A local church started a generator-powered kitchen for the Entergy crews that arrived to restore power as well as anyone else who needed to be fed. The county Office of Emergency Services sent pallets of drinking water to our community center where it was distributed to our residents, none of whom had water since the power was out. Everyone pulled together to clear the roads, all of which were impassable after the storm.

The damage to the timber on our farm was almost overwhelming. Almost every tree was damaged, and many were uprooted or had the tops entirely broken out. The big red oak in our yard lost probably one-half of its limbs, which were now lying in a tangled pile all around the base of the tree. Our 4X4

clothesline poles broke off when a branch fell on the lines. Our canoe was smashed when a five-lb pine branch coated with 75 lbs of ice fell on it. Our boundary fence and all of our cross fencing was flat on the ground where trees had fallen on them. It took Austin and I two hours and two tanks of chainsaw gas to cut a path to our mailbox just wide enough to drive through.

As soon as work with the Fire Department slowed down we went to work trying to clean up the horrific mess on our farm. A group of dear friends came out one Sunday and we cleaned up the pine grove close to the house. I started cutting and piling up pine logs that were big enough to saw into lumber. Luckily I had a band saw sawmill on the place. Over the next six months I sawed over six thousand board feet of lumber from the trees that were destroyed by the ice storm.

It’s been over three years now since the Great Ice Storm. The trees that fell are gone now, but the stumps remain to slowly rot away. The fences are repaired, I’ve fixed the barn roof that was damaged by a hickory tree that fell on it, and I’ve sold most of the lumber that I sawed from the logs I collected. Still we are reminded every day about the ice storm of ’08. All you have to do is look at the woods and see all the broken branches hanging everywhere. It will be a long time before the woods recover from this disaster.

Adding on

Back in the 1980’s when we built our log house, we were somewhat restricted in the size of our house because we were building with logs. We also didn’t feel like we needed a very big home. A bigger house just meant more space to heat and keep clean, plus we didn’t have much cash for building materials and we were unwilling to borrow money for our project. Although I wanted a bathroom, it has always seemed uncivilized to me to have a commode inside, and we were pretty happy with our outhouse. Most folks, though, for some reason, seem to want their commode inside the house. As we get older we have come to grips with the fact that someday someone else is going to be living in this house, and chances are they will want to defecate indoors (sounds disgusting, doesn’t it?).

I realized that the next occupant of this place will tack a bathroom on our log house—probably something that looks like an addition, most likely a frame room stuck on the side of our house. To keep myself from rolling in my grave when that happened, I decided to build a log addition that would look like it belonged with the rest of the house. While we were at it we thought we would build a bigger bedroom with good cross-ventilation and a sleeping porch. The plan we came up with would be a 20X24-foot log pen on the North side of our house, divided into a 12X20 bedroom and a 8X14 bathroom with a tiled shower, a vanity, and an actual flush commode!

In December of 2008 I cut the timber for our logs, borrowed a portable sawmill and milled the logs that we would need. The mill I borrowed wouldn’t cut the longest logs, which were 24 feet six inches long, so I hauled these logs to my friend Gary’s mill and we cut them there.

Once the logs were milled, stacked and drying, I borrowed a backhoe and dug the hole for the foundation and cellar. This I did in January of 2009,

intending to build the foundation that summer. My plans were changed by the Great Ice Storm (see related article in this blog). We did get the footing poured that summer, but because of the ice storm cleanup it would be a year before the foundation would get built. This project was delayed until the spring of 2010. We wanted

to lay up a stone foundation, so we used the same backformed masonary technique we used when we built the house. This involves building a straight and plumb plywood form, laying the stone so each rock face is 12 inches from the form, then filling in behind each course of rock with concrete and reinforcing wire. Maria would pick the

stone, Austin would mix the mortar or concrete, and I would lay in the mortar and stone. Most nights I’d be out there about ten o’clock with a flashlight finishing the joints. Before we finished the front wall we set a 1000 gallon cistern in the hole. This doubled our water storage and hopefully would

prevent us from ever hauling water again. We finished the foundation in early November, just about the time the weather

got too cold to do rockwork.

In the spring of 2011 Austin and I set the oak beams that span the basement, and I put in the joists and subfloor so we would

have a platform for raising the logs. We started up with the walls on the first of June, which also was the day that it got really hot, and stayed that way for the rest of the summer.

I would load several logs on my trailer and pull it into the drive-through in our barn so I could do my notching in the shade. Once I had a log dovetailed, I would pull the trailer out and move the log to my 12-inch joiner, which is powered by my 1939 Allis Chalmers tractor via flat belt. A couple of passes would plane the log down to clean wood. Then I would pick the log up with the forks

on the front-end loader of my Belarus tractor and move it to the building site’ where the boys and I would wrestle it into place. Then

back to the barn to lay out another notch. Austin and Jed were a great help to me that summer. I don’t know how I could have done it without them.

By the first of September the walls were up. Next came the pole joists and rafters, then the 2X6 tongue and groove roof decking. Full size 2X4’s set on edge made

a space for the 3” foam insulation, then 1X4 lath across the 2X4’s and finally, towards the end of October, the metal roof went on. “Let it rain”, says I—“we have a roof!” It had

been a long, hot summer but we finally had something that looked like an addition to our home. A good coating of redwood-stained CWF brought the logs to nearly the same color as our original house.

The winter was spent siding the gable ends, finishing the sleeping porch deck and adding soffits, gutters and downspouts. In the spring I began the challenging job of chinking the exterior. This involved cutting plasterers’ lath (expanded metal also known as “blood lath” because it is very sharp, and shreds your fingers) to fit the space where the chinking will go. After it is stapled in place it is filled with a mortar mixture, then worked to the right shape with a small trowel. That summer I planed down a bunch of the side lumber that came off the logs when I milled them and made tongue and groove paneling for the inside gable end above the north bedroom wall. Lately we put in the ceiling for what will be our bathroom and are now adding a ½-inch subfloor to the existing ¾-inch subfloor so that the finish ¾-inch flooring will be the same height as the floor of the house. Next I will frame the wall that will divide the two rooms and start the plumbing and electrical work.

After I wrote that last paragraph a lot has happened. . Through the winter of 2012/13 I framed the wall between the bedroom and bathroom and put in all the plumbing for the bathroom. My buddy Frank graciously volunteered his time as an electrician, so we got the whole thing wired. Through the summer I insulated the cracks between the logs (outside chinking was done) with that expandable foam in a can. It took a couple of cases but this method really makes a tight seal between the logs so no air can infiltrate the chinking. Then came the whole chinking thing again, this time on the inside.

While all this was going on, Maria was working her magic with tile in the bathroom. I built a curb with rounded edges out of treated lumber and she laid a beautiful mosaic scene on the shower floor, then went up the back of the shower with a scene of cat tails, reeds, a duck, and more. When the shower was finished and the interior wall was sheet rocked and painted, I trimmed the interior windows and doors with ash lumber that I’ve been saving for years. It is from the tree that fell on the Hogan back in ’08 or so. I milled the lumber back then, all I had to do now was dig it out of the stack and plane it to size. I also used the ash to build a cabinet to go under the bathroom sink.

By now it was late July of 2013. We decided to blow off our planned vacation (again) and finish the addition enough so we could move in. Rather than make my flooring from scratch like I did on the house, I actually bought finished ash flooring from a place in Melbourne. It took a few days to nail it down but boy does it look great! A few more days installing baseboard and trim and we were ready to move in. What a difference from our old stuffy bedroom. The new one is big and airy and soooooo comfortable. We love it, and we also love our nice spacious shower and Maria REALLY loves that flush commode!

The big pine

August 19th, 2012—Today I cut down one of the Grandfather trees on our farm. This giant yellow pine must have been one of the first to sprout when the sorghum field that is now our pine grove went fallow back in 1936. It stood just outside of our front gate, providing a fair amount of shade during the morning hours.

We’ve been losing a lot of pines that were damaged by the ice storm in 2009 and then stressed even more by last years’ hot dry weather and then the extended drought and heat of this summer. I first noticed some dead

branches on it last spring, which I removed with the help of a boom truck. Lately, though, the rest of the tree has turned brown and I knew there was no hope last week when I heard the unmistakable scritch scritch of southern pine borers under the bark. They only attack dead trees.

With a heavy heart I set out to bring the big pine down while it is still in good enough shape to make some quality lumber. First I shot an arrow with a long nylon string attached over the lowest branch, about 30 feet up. I used the line to pull a larger rope up so we could pull the tree in the direction I wanted it to fall. There was a fair chance that it would fall on our picket fence or house if I

didn’t direct the fall. With Austin ready to pull on the rope I fired up the old Husky and went to cutting. When cut almost all the way through the tree settled back and pinched the blade, even with Austin and Maria pulling has hard as they could. I drove an axe head into the kerf to unstuck the bar, cut pretty much all the way through, then ran over to Austin and Maria and helped them pull it over. It made quite a crash when it fell. After limbing it I cut two BIG 14-1/2 foot logs plus another good-sized 12-footer. The top 12 feet had lots of big knots, so it went to the brush pile.

At 24 inches above ground level the stump measured 23-1/2 inches. The small end of the first 14-foot log measured 18 inches. This was a big ol’ tree.

I marked the stump with three tacks. The one in the middle represents the year 1936, when this tree was just a sprout. The next tack is 1951, the year I was born. At that time the tree was about seven inches in diameter. The tack on the far left was 1973, the year I bought this land. It would have

been about a 14-inch tree at that time.

We’ll miss that tree. We are going to put a really big flat rock on the stump for a while, then when it is too rotten to support it I’ll dig it out and plant some new tree in it’s place—maybe an ash or other good shade tree. Hopefully some day a big beautiful tree will stand again in that spot.

The Old Rock Trailer

January 26, 2013 Yesterday, when I was about halfway through tearing apart my old rock trailer, I got to thinking that the story of it’s last 30 years might be of some interest, and if I didn’t write it now it would be lost forever. I walked to the house and got my camera and took this photo, as far as I know the only one ever taken of this thing that has done so much work for me in past years.

About 30 years ago I repaired a saddle for Robert Linville, a local rancher. When I delivered the saddle to the shed where Robert kept his tack, I saw this little home-made 4X6 wooden trailer lying unused in the weeds, and thought that it would be just the thing to pull behind my newly-acquired 1937 John Deere Model “B” tractor. Robert was only too happy to trade me the trailer for the saddle repair.

The trailer was at that time probably 30 years old, built of oak on the front axle of an old truck, probably a 20’s or 30’s model. The wood was weathered but still fairly sound, but the tongue was in pretty bad shape. I hooked it to the bumper of my ’51 Chevy truck and pulled it home. At this time we were preparing to start on our log home—the one we live in now. As I was planning on building my own foundation I needed rocks—lots of them. The trailer was put to work right away, groaning under huge loads of field stone, some rocks weighing in excess of 200 lbs. The rocks came from all over the farm, but mostly from the area I called The Park, which is the watershed of our spring, and involved a pretty steep climb over very rough ground. The trailer hauled many, many tons of rock, which I piled up around the footing of what would be our new home. After a few months of this abuse, the rotten tongue finally gave way, and it was time for a rebuild.

About this time I hauled a load of trash to the landfill near Mountain View. I always enjoyed a visit to the dump. Being a true scavenger at heart, I often came home with a bigger load than I left with, and this day was no exception. In the dump I found a pile of interesting boards—2X6’s about 10 feet long, very worn and chewed up on one side, the other side weathered but still showing a coat of old yellow paint. They looked to be some sort of hardwood, so I loaded them and took them home, figuring that as long as I was replacing the tongue I might as well use this lumber for the bed of the trailer.

For the tongue I used a full-size 2-1/2 by 6 piece of heart-cut white oak. When I made the first cut in my new-found dump lumber I was surprised by how red the wood was—even redder than red oak. I took a chunk of it down to my shop and started peeling off the yellow-painted side with a hand plane. Imagine my amazement when I found that I was working with Philippine Mahogany! It took some thought before I realized where the boards had come from. At this time the Sylamore ferry was still in operation, ferrying traffic on Highway 9 across the White River north of Mnt. View. When the ferry was built they apparently used mahogany lumber for the deck boards, as it is impervious to water and rot. Since then I’ve always said that I’ll bet I have the only mahogany rock trailer in Stone County, Arkansas.

When the John Deere tractor was replaced by a 1939 Allis-Chalmers“B” model I continued to use the old trailer for hauling rock, firewood, fenceposts, whatever. Ten or twelve years ago I bought a Belarus tractor with a front-end loader. I no longer needed a trailer, so most of the time it has been parked out behind the barn. Yesterday, in a rare fit of farm cleanup, I decided it was time to scrap my old friend out. Tonight we are burning fresh-split mahogany in the cookstove, and the axle and wheels of my old trailer are in the iron pile, ready for a trip to Sol Alman’s scrap yard the next time we go to Little Rock.

The Guest Cabin

Gallery

This gallery contains 9 photos.

When the Great Ice Storm hit (see The Ice Storm post) I had some really big yellow pine trees down, and a bandsaw mill on site.. When I sawed up all the logs that were down, I saved the best … Continue reading

Truck #12

In the summer of 1974 I was back in my hometown of Roscoe, Illinois, staying at my parents house and working as a cement truck driver to make my yearly land payment, which was due in November. Out behind the redi-mix plant was a rusty, blue 1956 GMC 3/4-ton pickup truck that apparently at one time had been part of a truck fleet, because painted on the side of the cab right behind the passenger door it said “Truck #12.

Most of the junk behind the plant belonged to the former owner, a local dairy farmer named Bill Dwyer. I asked him about it, and he said he would sell it because the body was rusted out too badly for it to pass State inspection. For $35 it was mine, complete with title. I poured a few gallons of gas in it and chained it to a cement truck and had one of the guys pull me, and as soon as I dumped the clutch it started right up, and ran pretty good. In October, when it was time to quit my job and head back to my land in Arkansas, I borrowed a towing hitch and pulled it south with the Chevy pickup that I was driving at the time. After several hair-raising adventures on the 600-mile trip, I arrived back home at Fox.

Truck # 12 served me well. I never licensed or insured it, but I put many the mile on that old truck, mostly around the Fox community, down to the Little Red River to visit friends, and occasionally to the county seat of Mountain View, keeping to the back streets to avoid scrutiny by the local gendarmes. The poor truck’s body was just a bucket of rust, eaten up by years on the salty Northern winter roads. First to go we’re both front fenders…..the left one I finished chopping off with an axe because it was starting to rub the tire, the right one fell off of its own accord down on the old railroad bed on the river. Both doors came off not too long after that, then the rear fenders. The truck still got a lot of use. When Larry Gundlack and I mixed the ferro cement for the roof of the Hogan, I borrowed an ancient old cement mixer and powered it by jacking up the right rear tire and running a flat belt from the tire to the mixer.

One day I was flying down the rough gravel River Road when I saw my friend John Vaughn standing in his yard. I slammed on the brakes to visit with him and I guess I blew a brake line because the pedal just went right down to the floor and stayed there. I don’t know why but I never bothered to try to fix the brakes–I just kept driving the truck, using the four-speed manual transmission to slow down, then shutting off the key to stop. I’m embarrassed to say that I used to come cruising in to the Fox store, downshift to 2nd gear, then turn off the key and step out of the truck (there was no door) before it came to a complete stop. I thought it was pretty cool, but in retrospect I’ll bet it freaked out poor old Joe Ticer, the storekeeper.

Finally after two or three years I needed an engine for my current ride, a 1953 Chevy truck, so I pulled the engine out of Truck #12. That wasn’t the end of the old workhorse, though. I took the bed and front axle off, put on a trailer hitch, and bolted on two oak six by sixes across the frame, and made a log and lumber hauling trailer. It has hauled hundreds of logs to the mill, and thousands of board feet of lumber home. I still use it a lot; it’s sitting out here right now with a couple of big red oak logs on it that I’ll be taking to the sawmill soon.

Water

Water has always been an issue for those of us who live on the dry ridges of the Ozarks. We are lucky to have a spring on our place, down on the southeast corner of our our south forty, and probably 90 or 100 vertical feet below the house. It’s not a very big spring, and in dry times it slows to a trickle but has never yet dried up completely. At some time years ago I dug it out and built a containment that pipes water to a concrete spring box that I built far enough below the spring to be full all the time. To this day we carry our drinking water from the spring to the house in gallon jugs. We used to carry four gallons at a time; nowadays we just carry two.

At first all my water got carried from the spring. In 1977 I hired old Webb Berry to bring his dozer and dig a pond below a wet-weather spring a little closer to the cabin, so at least we didn’t have to carry wash water so far. In 1981 I had a well dug about 50 yards south of the cabin. It was 110 feet deep and never was a very good well. I put a sucker-rod pump on it, the kind with the long handle on it, and it was a chore working it because the well only filled about a quarter of the way and that’s a long way to lift water. After a few years I got a pump jack with a 5 horsepower gas engine, which was a big improvement. Water wells are an iffy thing in these mountains. At best I would get 25 gallons of water per day, and it had a lot of iron in it. I built a water tower next to the well with two 55-gallon barrels on it. Next to that I built a screened in gazebo with a wood-burning hot water heater, an old gas range, and an even older gasoline-powered Maytag wringer washer. The building became our wash-house and canning kitchen. For many years every morning I would pump water, then carry two 5-gallon pails of it to the cabin. When you have to carry your water you learn to be very frugal with it.

When we built our new log house we entered the modern age. We put a 1000-gallon cistern under the house, and installed gutters to catch all the rainwater that came off the roof. I calculated that 1.2 inches of rain would amount to 1000 gallons of water in our cistern. A 12-volt diaphragm pump and pressure tank give us running water in kitchen and bathroom. I invested in two stainless steel German-made Wisi filters to keep crud from the roof from getting into the cistern. I built my shop over the drilled well. It is still there if we ever need it.

1000 gallons sounds like a lot of water, but with a family of four we would occasionally run out of water during long summer dry spells. When we added on our new bathroom and bedroom we put another 1000 gallon cistern under the addition, and since then we’ve always had plenty of water.

At our pond, in the summer, there is a solar array that drives a Shurflo 12-volt diagram pump. Whenever the sun shines on the panels water is pumped about 85 vertical feet to a 1500 gallon tank not far above the house. This water is piped to hydrants in our yard, garden, and orchard for use during the dry summer months. For our livestock we catch water from the barn roof in troughs. A few bass fry from the pond control mosquitoes in those tanks.

We’re really happy to be self-sufficient with our water. Our spring water tastes so much better than the treated stuff from the local community water system, and that’s still another bill that we DON’T get!